Gyrfalcon

General Description

The Gyrfalcon is the largest falcon in the world. Despite its size, it maintains a falcon-like profile with a long tail and long wings. Its wings are broader and more blunt at the tips than many other falcons. The plumage of the Gyrfalcon can take three main forms, white, gray, and dark, with many intermediate plumages. White adults have almost pure white breasts and bellies. The rest of their bodies are white mottled with brown. They have dark wingtips. Gray adults have gray upperparts with subtle darker mottling, and white underparts mottled with gray. Dark adults are dark-brownish overall above and brown streaked with white below. There is extreme sexual size dimorphism among Gyrfalcons, with males being only about 65% the size of females.

Habitat

The Gyrfalcon's distribution is circumpolar. Gyrfalcons inhabit Arctic regions, from the northern coastal tundra to the edge of the boreal forest. They are often found in open areas with cliffs, and along rocky coasts and rivers. Wintering habitat tends to be more wide open.

Behavior

Gyrfalcons are powerful flyers and pursue their prey in flight until overtaking them. They also locate prey while perched or in flight.

Diet

Large birds including ptarmigan and waterfowl are the most common prey item of the Gyrfalcon. They also eat rabbits, voles, small birds, and other mammals.

Nesting

Monogamous pairs nest on the ground or on cliff ledges, sometimes in old nests of other birds. They do not build a nest of their own. Both adults incubate the 3-4 eggs for about 35 days, although the female incubates more than the male. The female broods the young for the first few weeks after hatching, while the male brings food. After the brooding period is over, the female also hunts. The young begin to fly at 45-50 days and become independent shortly thereafter.

Migration Status

Many Gyrfalcons remain in the far north year round, but the most northerly breeders are migratory. Immatures tend to move south in winter more than adults, and more of the birds seen in Washington are immature. The same may be true for females, as most of the birds banded in Washington (adult and immature) have been female.

Conservation Status

In some parts of the world, Gyrfalcons are threatened by the falconry trade. While populations in some regions are considered threatened, the Gyrfalcon appears stable in North America where its range is fairly remote from human disturbance. In Washington, numbers have increased in newly irrigated farmlands in the Columbia Basin, but this may be a result of newly created habitat rather than an increase in population.

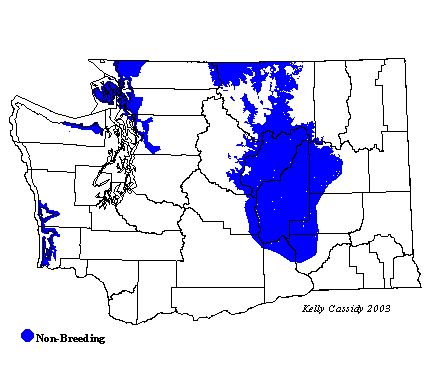

When and Where to Find in Washington

Gyrfalcons are rare visitors to open Washington lowlands from mid-October through March. In western Washington, the Samish Flats (Skagit County) is a good place to see them.

Abundance

Abundance

| Ecoregion | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oceanic | ||||||||||||

| Pacific Northwest Coast | R | R | R | R | R | R | ||||||

| Puget Trough | R | R | R | R | R | |||||||

| North Cascades | ||||||||||||

| West Cascades | ||||||||||||

| East Cascades | ||||||||||||

| Okanogan | ||||||||||||

| Canadian Rockies | ||||||||||||

| Blue Mountains | ||||||||||||

| Columbia Plateau | R | R | R | R | R |

Washington Range Map

North American Range Map