Turkey Vulture

General Description

The most widely distributed vulture in the New World, the Turkey Vulture is a large, predominantly blackish-brown bird. It is most commonly seen soaring overhead. The Turkey Vulture has a 5- to 6-foot wingspan and soars with its wings tilted up, in a dihedral pattern. Turkey Vultures rock back and forth when soaring. The underwings are two-toned: silvery flight feathers with black wing-linings. The undertail is also light. Juveniles have gray heads while newly hatched birds have black heads. When the birds are soaring, it is difficult to see the color of the head. The rocking, as well as the dihedral pattern, distinguishes the Turkey Vulture in flight from other large, soaring birds. Perched, adult Turkey Vultures are unmistakable, with their featherless, red heads.

Habitat

Turkey Vultures can be seen soaring over a broad variety of habitats. They are most often found above open country, especially within a few miles of rocky or wooded areas. Rocky outcroppings, cliffs, and dry forests provide nesting sites, while open areas are prime foraging habitat.

Behavior

Unlike most birds, Turkey Vultures have a well-developed sense of smell. As they soar over foraging areas, they scan the ground, searching for carrion or scavengers that might signal the presence of something dead. When they locate food, they eat it in place. They usually forage alone, but sometimes congregate around food sources. In the Pacific Northwest, they roost communally in small groups. In the eastern US, several thousand birds may nest in the same area.

Diet

Turkey Vultures are scavengers, eating nearly any carrion they find. They prefer fresh carrion and appear to specialize in small food items, especially where their range overlaps with the dominant Black Vulture, a species that does not occur in Washington. They cannot open large carcasses.

Nesting

It is not known when Turkey Vultures first form pair bonds and breed, but they do form long-term bonds. Pair formation includes a ritualized display with several birds in a circle on the ground, hopping up and down with wings partly spread. Nests are located in sheltered areas, such as hollow trees or logs, in cliffs, caves, dense thickets, old buildings, or any secluded area isolated from humans. They build little or no nest and lay 1 to 3 eggs on the ground or the bottom of the nest area. Both male and female help incubate the eggs for about 28 days; both have brood patches. Once hatched, the nestlings are brooded almost continuously for the first five days. The male and female take turns brooding the young, allowing one parent to collect food that it then regurgitates for the young. The young first begin to fly at about nine or ten weeks. The fledging process is gradual and varies depending on nest location. Birds fledging from lower sites have the luxury of taking short practice flights for a few days before taking extended flights. The first flight of young birds that hatch in exposed or elevated nests will generally be extended, since short hops are sometimes too risky for them. Once the young begin to fly, they generally spend 1 to 3 more weeks at the nest site, taking advantage of the food provided by their parents.

Migration Status

Turkey Vultures are considered partial migrants. Those birds that breed north of the wintering grounds usually migrate. Many birds from Vancouver Island, British Columbia and northward gather at the southern tip of the island in late summer. Once gathered at this staging area, large groups of up to 400 birds travel across the Strait of Juan de Fuca to the Olympic Peninsula, and then southward on to California and South America. Their final destination is unclear. They begin returning to Washington in February.

Conservation Status

The status of the Turkey Vulture population can be difficult to determine. They may travel great distances each day, and are often clumped at roost sites. Turkey Vultures can accumulate pesticides and other contaminants, which are a potential threat to their population. Other threats include accidental trapping, collisions with cars, electrocution, shooting, and lead ingestion from eating animals that were shot. They were formerly persecuted in agricultural areas because they were suspected of spreading livestock diseases such as anthrax and of preying on young animals. Since it is now understood that these suspicions are groundless, much of the persecution has ceased. Turkey Vultures have benefited from their adaptability in diet and nest sites, and their population appears to be stable or increasing.

When and Where to Find in Washington

Turkey Vultures can be seen soaring over a wide range of habitats throughout Washington from February to October. In western Washington they can often be seen in the Snoqualmie Valley (King County) and in the Willapa Hills (Pacific County). Wintering birds are rare throughout Washington. During migration they are most common through the Puget Trough area; east of the mountains their migration is on a broad front. Breeding Turkey Vultures are found in the lower forest regions in the western Cascades and are common in the lower forest and adjacent steppe along the eastern Cascades. They are uncommon in the northeastern corner of Washington. Migrants are seldom seen in the Blue Mountains, and breeders have not been reported there. Turkey vultures are uncommon along the outer coast, but probably breed there in small numbers as they do in the foothills of the Olympic Mountains. Turkey Vultures are uncommon to rare in the drier portions of the Columbia Basin, even as migrants.

Abundance

Abundance

| Ecoregion | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oceanic | ||||||||||||

| Pacific Northwest Coast | U | F | F | F | F | F | C | U | R | |||

| Puget Trough | R | U | F | F | F | F | F | C | F | R | ||

| North Cascades | U | F | F | F | F | U | ||||||

| West Cascades | U | F | F | F | F | F | F | R | ||||

| East Cascades | U | F | F | F | F | F | F | U | ||||

| Okanogan | U | F | F | F | F | F | F | U | ||||

| Canadian Rockies | U | F | F | F | U | U | ||||||

| Blue Mountains | R | R | R | R | R | R | U | U | ||||

| Columbia Plateau | U | U | U | U | U | U | U |

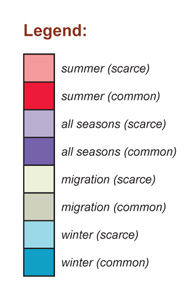

Washington Range Map

North American Range Map