Sandhill Crane

General Description

Sandhill Cranes are big birds, with long legs and necks, long pointed beaks, and wingspans which can be over six feet. Adults are gray with red crowns. Juveniles are gray, washed with brown. During the breeding season, the gray plumage of the adults is often stained brown with mud. A "bustle", which covers the short tail, is composed of long, drooping inner wing feathers (tertials and inner secondaries.)

Habitat

Sandhill Cranes live in wet meadows and grasslands, and they feed in grain fields and pastures. In Washington, they nest in wetlands in areas that are surrounded by Lodgepole Pine, Ponderosa Pine, Grand Fir, or Douglas Fir forests. Emergent vegetation is a key component of their preferred nesting areas. During migration and in winter they live in more open prairie, agricultural fields, and river valleys. Sandhill Cranes prefer to live in habitats where they have clear views of their surroundings.

Behavior

During the breeding season, Sandhill Cranes paint themselves by preening mud, which serves as camouflage, into their feathers. The courtship rituals of cranes are elaborate: paired birds spread their wings and leap repeatedly into the air while calling. Pairs return to the same nesting territories year after year and sometimes use the same nest repeatedly. The young learn migratory routes from adults; without this modeling, they do not migrate.

Diet

Sandhill Cranes are omnivores; their diet varies by location and season. They eat insects, rodents, snails, small reptiles and amphibians, nestling birds, the roots of aquatic plants, tubers, berries, seeds, and grains.

Nesting

Nests are built in emergent vegetation in shallow water or close to water. Both parents build the nest, a mound of plant material pulled up from around the site and anchored to surrounding vegetation. Both parents incubate the two eggs. The young leave the nest within a day of hatching and follow their parents out into the marsh. At first, both parents feed the young, but the young quickly learn to feed themselves. They remain with their parents for their first nine to ten months.

Migration Status

There are six recognized subspecies of Sandhill Cranes. Of these, half are migratory. The migratory cranes travel long distances, using routes learned from adults. During this migration they congregate at major stopover spots. The subspecies of Sandhill Crane seen in Washington are migratory. Most of the cranes that breed in Washington are members of the Central Valley population of the Greater Sandhill Crane subspecies, and they winter in the Central Valley of California. Members of the other two migratory subspecies, Lesser Sandhill Crane and Canadian Sandhill Crane, breed to our north and only migrate through Washington. Breeding Sandhill Cranes arrive at their nesting grounds in early March and leave for California between late September and mid-October.

Conservation Status

Although with over 500,000 birds the Sandhill Crane is the most abundant crane worldwide, it is an endangered species in Washington. Its low numbers in the state, limited distribution, and low reproduction rate, and the loss of suitable crane habitat put it at significant risk of extirpation in the state. As an added risk, a large percentage of its wintering habitat is privately owned and thus subject to alteration without concern for endangered species. The small population of the Sandhill Cranes that breed in Washington are members of the Greater Sandhill Crane subspecies, which numbers only 70-80,000 birds throughout its entire range.

Sandhill Cranes formerly bred commonly in wetlands on both sides of the Cascade Crest but now breed in only two or three places in eastern Washington. They are limited by the availability of large tracts of undisturbed marsh and meadow for nesting and feeding, with adequate water levels during the nesting period. Sandhill Cranes are extremely wary, requiring isolated sites with good cover during the nesting period. When repeatedly disturbed by pedestrians, construction, low-flying aircraft, vehicles, or predators, they desert their nests. For Sandhill Cranes to survive in Washington, breeding, migration, and wintering habitats all need to be protected and enhanced. It is crucial that the loss and degradation of wetlands in Sandhill Crane nesting habitat is stopped, and in some cases, creation of additional habitat should be considered. Wetlands within two miles of agricultural areas providing grain are ideal roosting areas.

When and Where to Find in Washington

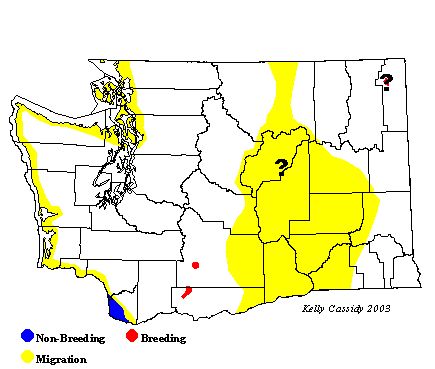

There are two confirmed nesting spots for Sandhill Cranes in Washington, one at Conboy Lake National Wildlife Refuge (Klickitat County) and the other near Signal Peak on the Yakama Indian Reservation (Yakima County). Cranes were first reported at Conboy in 1975, when a single pair nested. Subsequently, a single pair was reported at Conboy each year until 1988, but from 1988 until 1996, 2-9 pairs nested there each year. In 1994 and 1995, another single pair of cranes was found nesting on the Yakima Indian Reservation, and in 1996, a second pair joined them. Sandhill Cranes were also recorded in June, 1996 at Atkins Lake in Douglas County, which may indicate a third breeding area, although breeding in this area was not confirmed. During migration, however, large numbers of Sandhill Cranes can be seen at stopover sites in the Columbia Basin. Sandhill Cranes migrating to northwestern Canada and Alaska stop in eastern Washington near Othello (Adams County) and west to Royal City (Grant County), with peak numbers reaching 15,000 in early April. After refueling, they often also stop near Mansfield (Douglas County) before continuing north through the Okanogan Valley. Some cranes migrate on the west side of the Cascades, moving north through the Puget Trough or along the coast. In the fall, cranes use similar routes to make their way south. Ridgefield National Wildlife Refuge and nearby agricultural fields in southwest Washington are regular wintering spots.

Abundance

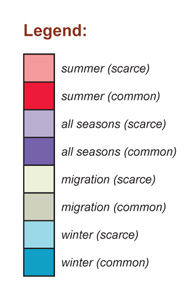

Abundance

| Ecoregion | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oceanic | ||||||||||||

| Pacific Northwest Coast | R | R | R | |||||||||

| Puget Trough | F | F | F | U | R | U | F | F | F | |||

| North Cascades | ||||||||||||

| West Cascades | R | R | R | R | R | R | ||||||

| East Cascades | R | U | R | R | R | |||||||

| Okanogan | F | U | R | F | U | R | ||||||

| Canadian Rockies | U | U | U | |||||||||

| Blue Mountains | R | R | ||||||||||

| Columbia Plateau | R | C | C | U | C | C |

Washington Range Map

North American Range Map